When the General Electric Co. was luring the brightest scientific minds to Schenectady early in the 20th century and bringing good things to life, it wasn’t always just about light bulbs, refrigerators and washing machines.

Many of those brilliant scientists and engineers — men such as Langmuir, Suits, Apperson and Schaefer — were also avid outdoorsmen, and for them and many like-minded people in the Schenectady area, pursuing their passion during the winter months usually involved putting on a pair of skis.

While skiing had previously been mostly a utilitarian endeavor — a practical form of transportation in heavy snow — that began to change in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. By the 1930s there was still very little recreational skiing, and no major ski resorts in the Adirondacks as we think of them today.

But when the sleepy little town of Lake Placid in the heart of the Adirondacks hosted the 1932 Winter Olympics, upstate New York was forever changed.

It was the first of four times that the Winter Olympics would be held in the U.S., and while there was plenty of bobsled competition and action on skates of various kinds — hockey, figure and racing — there was no downhill skiing. There was, however, cross-country skiing and ski jumping, and when a group of Schenectady people returned from the Games that year, the experience proved inspirational. Thus was born the Schenectady Snow Train.

“My father had heard about snow trains that took people from Boston up into New Hampshire to ski in 1931 and ‘32,” said James Schaefer, whose father, Vincent, became well known in the field of atmospheric science after World War II. “A group of them came back from the Placid Olympics and were all excited to form their own snow train. They tried in 1932 and ‘33, but much like this year there wasn’t enough snow. So they spent all of 1933 preparing for 1934.”

Skiers ride the rope tow at the North Creek Ski Bowl in the mid-1930s. One of the first mechanical lifts in the United States, it was built by Schenectady's Carl Schaefer. The Schenectady Snow Train transported first-generation downhill skiers from the Electric City to the Adirondack hamlet.

And on March 4, 1934, skiers — 378 of them — climbed aboard a Delaware and Hudson train in Schenectady and rode the 60-mile trip by rail to North Creek.

This winter, some 90 years later, that historic train ride and some of the skiers aboard that day are being celebrated for their place in winter-sports history.

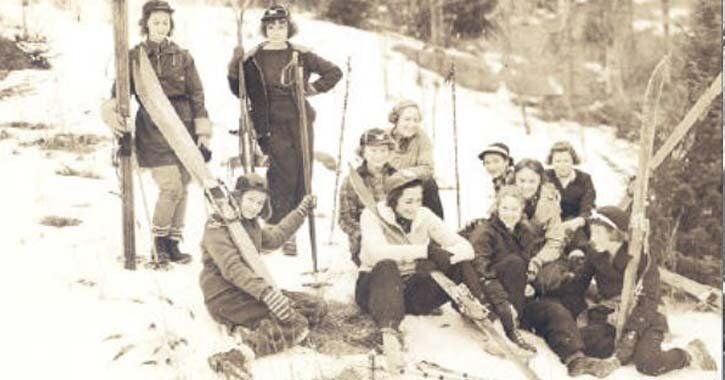

This Tuesday at 6 p.m. at Wolf Hollow Brewing Company in Glenville, Schaefer will give a talk titled “Winter Women,” telling the story of two women he knew well who were on that train. He will also look at the efforts of his father and his uncle, Carl, to put together that first excursion. It is one of a series of events being held in February and March at Wolf Hollow and the Tannery Pond Center in North Creek to help celebrate the anniversary of the snow train.

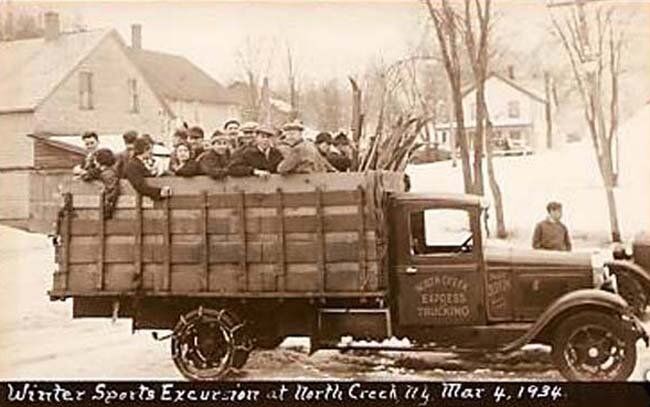

Skiers are transported between the Schenectady Snow Train and a nearby ski hill near current-day Gore Mountain in March 1934.

The title of Schaefer’s presentation refers to the role played by his mother, Lois Perret Schaefer, and Freddie Anderson in the creation of the snow train and the rapid increase in interest in skiing over the next three decades. Anderson was just 13 at the time but went on to create the Schenectady Ski School, initially at Schenectady Municipal Golf Course and then Maple Ridge Ski Area in Rotterdam. Perret, meanwhile, was the designated “nurse” on the first snow train and many subsequent railroad excursions up north, and helped create guidelines sponsored by the Red Cross and later used by the first National Ski Patrol in 1938.

“Freddie’s father was a doctor at Ellis Hospital and they took the train to the Lake Placid Olympics in 1932, and were also on the first snow train to North Creek,” said Schaefer, who started skiing with his parents and other family members in the Rotterdam and Glenville hills, spending many snowy days getting to the top of Mt. Yantapuchaberg on the south side of the Mohawk River and Touareuna to the north. “Freddie was an incredible skier and still skiing in her 90s. My mom was one of the founders of the Mohawk Valley Hiking Club in 1929 and that’s how she met my father. A lot of skiers in the early days of downhill were getting hurt, so they felt it was very important for those on the train to have a first-aid plan to get skiers down the mountain. My mom was in charge, so she grabbed a group of skiers and put them through some Red Cross training.”

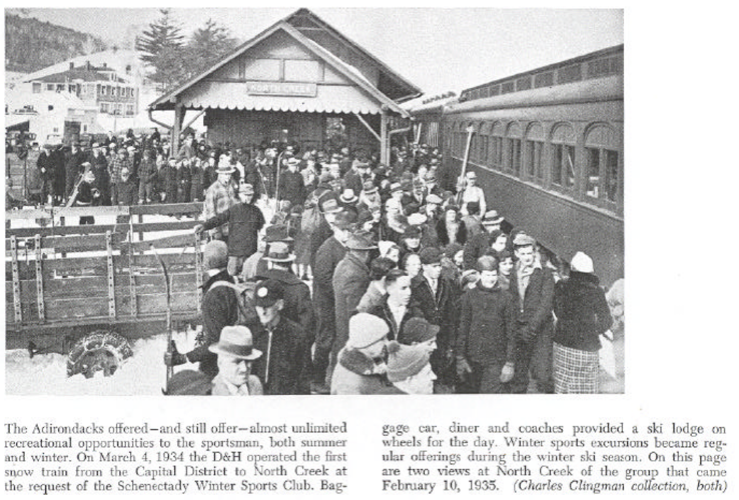

Winter sports enthusiasts stand outside the Snow Train in North Creek during the train’s second winter of operation in 1935.

It was the Schaefer brothers, Vincent and Carl, who selected North Creek as a destination for the Schenectady Snow Train in 1934. With 378 passengers aboard paying $1.50 for a round-trip ticket, the train left Schenectady at 8:14 that morning and arrived in North Creek at 10:30 a.m. With a little help from the locals, skiers were taken by truck to the trails atop Pete Gay Mountain, near today’s Gore Mountain Ski Resort.

Happy with the turnout for that first trip, the Schaefers, who had also just started the Schenectady Wintersports Club a few years earlier, set out to make the experience even better. By the following winter, Carl Schaefer — after venturing over to Woodstock, Vermont, to check out New England’s first official rope-tow lift — created the first rope tow in New York at North Creek. The advent of the rope tow, as well as advances in the manufacturing of skis and boots, sparked a surge in downhill skiing, according to Seth Masia, president of the Skiing International History Association.

“The rope tow really made a difference. It was quite a novelty at the time, and the equipment changed drastically over a five-year span around that time,” said Masia from his home near Boulder, Colorado. “Along with that, the steel edge was patented in 1928, new bindings became available and the first chairlift in the U.S. [Sun Valley Resort in Idaho] was opened in 1936. All skiing had been a free-heel thing, but with new boots and bindings it became a whole lot easier to control skis.”

The North Creek Train Depot was a busy place on weekends after the start of the Schenectady Ski Train in 1934. Passengers were transported from the station to the nearby ski hills via automobile.

Masia, who covered the 1980 Winter Olympics in Lake Placid for Ski Magazine and was a 2023 inductee into the Colorado Snowsports Hall of Fame, said that while competitive downhill skiing started just after the turn of the 20th century in Kitzbuhel, Austria, it wasn’t like it is today.

“In 1906, skiers half-expected to fall down once or twice during a race and then get up and finish,” said Masia. “The track was unprepared and a run that took eight or nine minutes back then is now done in 90 seconds. These days when you fall during a downhill race, you don’t get back up and finish it and maybe win it. That just doesn’t happen.”

Former Gazette reporter Bill Rice, who wrote a ski column for nearly 40 years at the newspaper, agreed with Masia that skiing was a much more difficult proposition when he, now 88, was a much younger man. He remembers watching a Warren Miller movie that made that abundantly clear. Miller directed 38 movies about the sport between 1950 and 1987.

A skier demonstrates the new Alberg Technique on a ski hill in Rotterdam in 1930.

“This was back in the 1980s, and Miller made a film showing current skiers on the slopes using the much older equipment,” remembered Rice. “They were good skiers but they looked like beginners on the older equipment. Things were so different back then. You didn’t have metal edges on your skis, just the wood, and on icy, hard snow the skis just didn’t react very well.”

Along with the new equipment, some Scandinavian skiers who came to work for GE in the 1930s began sharing some secrets about technique with their Schenectady colleagues. In his first Gazette ski column in 1934, C.G. Suits, another GE scientist, explained the Arlberg technique to his readers and talked about the sport’s increase in popularity.

“Is skiing any different from the climb-up-hill and slide-down-hill skiing that we did as youngsters?” asked Suits, a Wisconsin native who came to GE in 1930 as a research physicist. “This last question should be answered with a positive ‘yes.’ Skiing has developed into a remarkably varied and fascinating sport.”

Irving Langmuir, who won the Nobel Prize for chemistry in 1932 while at GE, was born in Brooklyn but learned to ski in the European Alps, and John Apperson, a Virginia native, moved to Schenectady near the turn of the century and worked at GE for 47 years. Both were avid skiers and even more dedicated preservationists, known for their work aimed at keeping state land out of private hands in the Adirondacks. Apperson was also the first person, according to many sources, to ski down Tuckerman’s Ravine on Mount Washington.

“Appy was my great uncle and started skiing around 1905, 1906,” said Ellen Apperson Brown, who has closely researched John Apperson’s life and produced a book in 2017, "John Apperson’s Lake George." “He probably got some pointers and encouragement from Eskil Berg and other Scandinavians who had come to Schenectady to work at GE.”

Apperson died in 1963 at age 84. By that time Whiteface (1958) and Gore (1963) were both open.

“The development of large, destination ski areas in the region starting in the 1950s and 1960s, along with all the television coverage of the 1960 Winter Olympics, helped create all the glamour around the sport,” said Phil Johnson, who succeeded Rice as the Gazette's columnist and just retired from the position last year. “Skiers like New Englanders Billy Kidd and Suzy Chaffee also helped popularize the sport, as did the evolution of clothing and ski gear, and really helped New York State make an investment in places like Whiteface and Gore.”

Apperson Brown agreed with Johnson’s assessment, but added that her great-uncle probably wouldn’t have welcomed all of the sport’s rising popularity.

“He spoke out against widening ski trails for competitive downhill skiing,” she said. “He was concerned that all the promoters of downhill skiing were building these commercial ski slopes on state land, land that was supposed to be protected by the Forever Wild clause.

“I remember that my uncle Jim, an engineer for GE, was frustrated, by the 1950s or so, that his uncle John was not in favor of downhill skiing,” added Apperson Brown. “There was definitely some conflict there.”

The Schenectady Snow Train kept running until the U.S. entered World War II, and was utilized again on a few occasions after the war by the Schenectady Wintersports Club.

“The roads improved, cars got better so the train became a little passe,” said Schaefer. “We kind of rekindled it for a couple of years in 2011. It wasn’t the same. But back in 1934 it was really something.”

Within a few years there were snow trains heading north from Albany and New York City, but it was Schenectady — thanks in large part to the Schaefer family and a host of their friends and colleagues — that got the ball rolling and changed the way we enjoy the Adirondack Mountains.

Snow Train and More

Tuesday, 6 p.m.: “Winter Women,” a presentation by Jim Schaefer at Wolf Hollow Brewing Company in Glenville.

March 2, 9:30-11:30 a.m.: A presentation on snowshoes at the North Creek Depot Museum in North Creek.

March 3, 3 p.m.: A Johnsburg community recording session and launch of the North Creek walking tour at the Tannery Pond Center in North Creek.

Through March 4: An exhibit of the 1934 Schenectady Snow Train and the history of skiing in the Schenectady County towns of Rotterdam and Glenville.

.